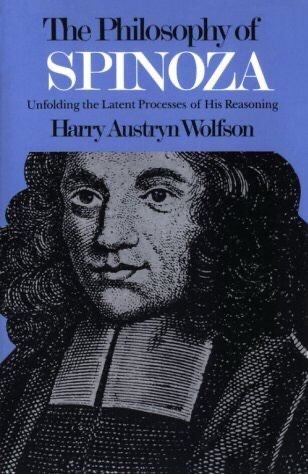

The Philosophy of Spinoza, Volume I

Reviews

No review yet. Be the first to review this book!

Description

The Philosophy of Spinoza, Volume I by Harry Austryn Wolfson is a monumental and scholarly exploration of the thought of Baruch Spinoza, one of the most significant philosophers of the early modern period. First published in 1934, Wolfson’s work is widely regarded as a landmark in Spinoza studies and an exemplary model of historical-philosophical scholarship. Across two volumes, Wolfson delivers a comprehensive, meticulous analysis of Spinoza’s system of thought, tracing its development, underlying influences, and systematic coherence. In Volume I, Wolfson focuses on the nature and structure of Spinoza’s philosophy, carefully reconstructing his metaphysical system. He situates Spinoza within the broader context of medieval Jewish and Islamic philosophy as well as the rationalist tradition, particularly the influence of thinkers such as Maimonides, Averroes, and Thomas Aquinas. One of Wolfson’s most important contributions is his argument that Spinoza’s philosophy should be read not only as a product of Cartesian rationalism but also as deeply rooted in the scholastic and theological traditions of the Middle Ages. Wolfson meticulously examines Spinoza’s Ethics, explicating key concepts such as substance, attribute, and mode, which form the core of Spinoza’s monist metaphysics. According to Spinoza, there is only one substance—God or Nature (Deus sive Natura)—which exists necessarily and is self-caused. Everything else in existence is a mode or modification of this one substance. Wolfson analyzes Spinoza’s rejection of Cartesian dualism, his redefinition of God as impersonal and immanent, and his radical denial of free will, emphasizing the deterministic nature of reality in Spinoza’s system. Wolfson also delves into Spinoza’s epistemology and theory of knowledge, explaining the three kinds of knowledge Spinoza distinguishes: imagination (or opinion), reason, and intuitive knowledge. He underscores Spinoza’s belief that true freedom comes through understanding necessity—the intellectual love of God is the highest form of knowledge and the path to human blessedness. Throughout the volume, Wolfson highlights Spinoza’s break from traditional religious doctrines, portraying him as both a rigorous rationalist and a profoundly ethical thinker. Spinoza’s God does not command worship or impose moral laws but is identical with the natural order itself. This naturalism, Wolfson shows, underpins Spinoza’s ethics, his theory of emotions, and his political philosophy. Harry Wolfson’s approach is systematic and thorough, often reconstructing Spinoza’s arguments by exploring their logical structure and historical roots. He offers an in-depth exploration of Spinoza’s method of demonstration, which follows the geometric model of Euclid, aiming for deductive certainty in philosophy. In summary, The Philosophy of Spinoza, Volume I offers an exhaustive and erudite study of Spinoza’s metaphysical and epistemological doctrines. Wolfson's scholarship situates Spinoza within both his historical context and the larger philosophical tradition, making this work essential for understanding Spinoza’s radical rethinking of God, nature, human freedom, and knowledge. It remains a definitive text for scholars and students of Spinoza and early modern philosophy.

May 03, 2025

May 03, 2025

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.png)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpg)